Think you’re fond of of graphing and computing stuffs? Great! Because you might remember this thing called theTexas Instrument TI-83from the old days. Sure, while programmable calculators in general are still pretty muchpopular these days, the graphing calculators from the21st-century are also coming in waves as we speak—potentiallydisrupting the market of scientific computing and educational technology.

In particular, there’s a certain education startup out there, relentlessly seeking to hijack our Internet browsers and mobile devicesinto a — should we say —graphing extravaganza. And it comes with a funky name as well:Desmos.

Yep. You’ve heard it right. As Greek-mythology-inspired as it sounds, Desmos actually has nothingto do with thegiant monster responsible for turningMount Olympus into rubble through the wrath of infernal flames. Instead, it is probably better known as an innocent-looking mathtool for the scientifically-minded, making applied math ever more palatableand entertaining!

Oh. Don’t believe in the mighty power of Desmos? Good job! Because it’ll then beour duty tobeg to differ, and attempt to convince you otherwise. Indeed, if at the end of the module you still find the scope of Desmos’ functionalitiesunappealing, then — and only then — shall we concede defeat and return to our ivory tower for more advanced Buddhist meditation training! On the other hand, if you’re just way toolazy to read the 12-page Desmos user manual, and are looking for more concrete examples to kick-start the creative process, then this oneis for you too!

Table of Contents

Graphing with Desmos

What isthe single word peoplethink of when theyhear online graphing calculator? Graphing of course! Indeed, this is something that Desmos does incredibly well — despite having a user interface that appears to bedeceptively simple. In what follows, we will seehow to wecan useDesmos to graph equations, functions and inequalities of different forms, beforeintroducing some bonus features such as graph segmentation,simultaneous graphing and animations!

Equations

When it comes to graphing, equation is one of those first words that comes to mind. On the other hand, it can also be construed as an umbrella term encompassinga plethora of mathematical objects such as explicit functions, implicit functions, parametric equations and polar curves. In what follows, we will illustrate how each of them can be graphed in Desmos — one stepat a time.

Preliminaries

Before doing any graphing though, we need to first learn how totype out a few mathsymbols that are frequently sought for. To that end, we have provideda partial list of common symbolssupportedin Desmos — along with their associated commands:

- The Multiplication symbolcan be obtained by typing

*(Shift+8on US keyboards). - The Division line can be obtained by typing

/(i.e., backslash). - $\pi$ can be obtained by typing

pi, and $\theta$ bytheta. The same goes other Greek Letters such as $\alpha$,$\beta$, $\tau$ and $\phi$. - $\sqrt{}$ by

sqrt, and $\sqrt[n]{}$ bynthroot(after which the value of $n$ can be adjusted manually). - Use the key

^(Shift+6on US keyboards) to createa superscript (e.g., $2$ in $x^2$), and the key_(Shift+Hyphenon US keyboards)fora subscript(e.g., $1$ in $a_1$). - The ceiling function by

ceil(), the floor function byfloor(), and the sign function bysign(). - The absolute value symbol by

|(i.e.,Shift+\on US keyboards).

For some commands (e.g., division, superscript, subscript), typing them out can move the cursor to the upper or lower area. In which case, youcan use the arrow keysto help younavigate around theexpression and type out what you want. Other times, you might need to use parentheses to group some of yourexpressions together — before they can be properly interpreted by Desmos.

Defining Functions

Traditionally, the most popular functions are the ones expressed in terms of $x$, which can be typed into a command line as follows:

\begin{align*} y = \text{some algebraic expressions in terms of }x \end{align*}

By reversing the roles of $x$ and $y$, functions in terms of $y$ can also be typed out into a command line as follows:

\begin{align*} x = \text{some algebraic expressions in terms of }y \end{align*}

So, what kinds of functions are supported in Desmos? Basically, all of the elementary functions you can think of! These include the 6 basic trigonometricfunctions, exponential/logarithmic functions (through the commandsexp, lnandlog), polynomials, and rational functions. In addition, the 6 basicinverse trigonometric functions— along with the 6 basic hyperbolic functions—are readilysupported by simply typing out the function’s name as well.

Now, if a function in terms of $x$ is meant to be referred on a repeated basis, then a name can be assignedto it by replacing the $y$ on the left-hand side with, say, $f(x)$. In a similar manner, a function in terms of $y$ can also be assigned a name as well, from whichwe can define and name acompoundfunctionin a command line — without having to resort to rewriting the expressions again and again:

- $y = 2f(3x-3)+e$

- $g(y) = \dfrac{\pi}{f(y)}$

- $f_1(x)= 55f(x)+43g(x) – 100 h(x)$

- $y = g(x)^2 \cdot \left( g(x)^{f(x)} \right)$

- $h(x) = 2 g(f(x)) + 3 g(f(x))$

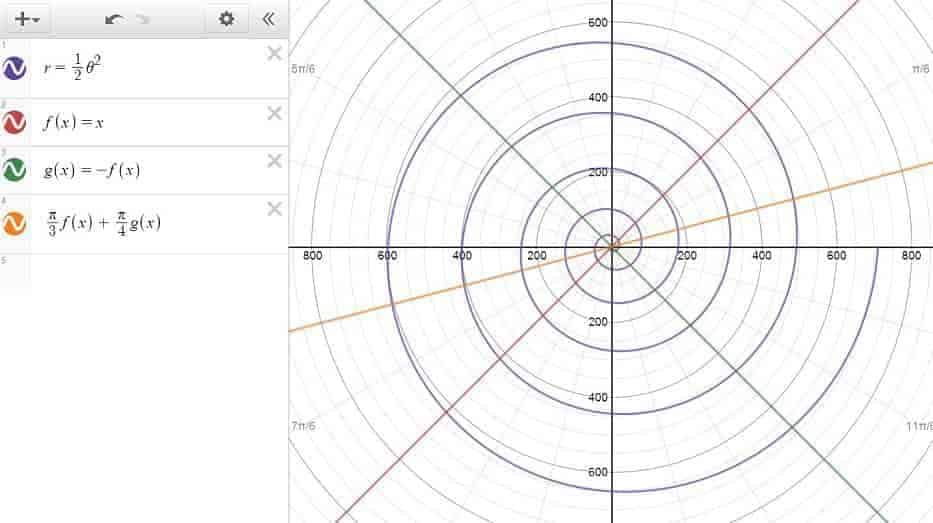

And in case you’re wondering, the polar functions are equally supported in Desmos as well. However, do note that in this case, the functions will have to be typed out using$r$ and $\theta$ as the designated variablesinstead (e,g., $r=\frac{1}{2} \theta^2$).

Calculus-Related Functions

As it turns out, Desmos is remarkably receptive to calculus-based expressions as well. For example, once a function in terms of $x$ is given, by attaching $\dfrac{d}{dx}$ in front of it, the graph of its derivative function can be readily produced — without having to resort to the explicit formula of the derivative. Similarly, the derivative of a function in terms of $y$ can also be graphed by appending $\dfrac{d}{dy}$ in front of it. Prettyneat, right?

Alternatively, if a function has already been assigned a name, we can alsouse the prime notation to denote itsderivative function (as in $f'(x)$). Apart from being easy to implement, the prime notationalso has the advantage ofbeing able to refer tohigher derivativesby simply adding a few extra $’$ (e.g., $g”$), which —comparing tothe repeated use of $\dfrac{d}{dx}$ — is definitely a plus to have.

Of course, if Desmos is good with the derivative functions, thenit shouldn’t a surprise that italso supports theintegral functionsas well. For the record, theintegral operator symbol $\int$ can be obtained by typing int into the command line, afterwhich you will have use the arrow keys to navigate around thelower/upper limitsand the integrand.

A note of caution though: when setting up an integral function —especially the ones involving multiple integral operators—you want totake that extra care to make sure that the variable of integrationis different fromthe variable(s) in the limits. In doing so, you are in effect removing yourself from the need ofpunching Desmos for real, in casethe expression doesn’tturn out to be exactly Desmos-interpretable. 🙂

Piecewise Functions

To define a piecewise function in Desmos, wecanuse the following syntax on a command line:

\begin{align*} y \ (\text{or }x) = \{ \text{condition 1}: \text{definition 1}, \text{condition 2}: \text{definition 2}, \ldots \} \end{align*}

As with other functions, a piecewise function can also be given a name by simply replacing the leftmost variable with the name of the function. This way,we can recycle the function repeatedlywithout having to redefine it ever again.

For example, let’s say that we are interested in defining the function $f$ as the sign function. That is:

\begin{align*} f(x) = \begin{cases} -1 &x<0 \\ 0 & x=0 \\ 1 & x>0 \end{cases} \end{align*}

then this would be the expression we want to type into thecommand line:

\begin{align*} f(x)=\left\{x<0:-1, x=0:0, x>0:1\right\} \end{align*}

which should produce the following figure:

In some occasions, it might be necessary to use the $\le$ and$\ge$ symbols to define a function accurately. In which case, just know thatthe $\le$ symbol can be obtained by typing out < and =in that order, and the$\ge$ symbol by typing out > and =, again in that order.

Other Equations

Since Desmos has its interface in Cartesian coordinates by default, it’s only natural that one woulduse it to plotequations expressed in terms of $x$ and $y$. In fact,implicit functions such asthat of a circle, anellipseor a hyperbolaare all very good candidates for this.

However, what is less clear is that Desmos can also interpret parametric equationsas well, provided that we type inthe equations for $x$ and $y$as if they werethe coordinates of thepoints instead (as in$(2\cos t, 3 \sin t)$ ), and that the variable $t$ — the designated variable for parametric equations in Desmos — is used throughout the expression. For some reason, Desmos simply won’ttake anyothervariable such as $x$ or $\theta$ for thispurpose.

On a more optimistic side, if you manage to type in aparametric equation the rightway, then you should be able see an inequality about the domain popping up right underneath the command line. Don’t take this for granted by the way, because this is whereyou get to configure the range of the variable $t$, which in essencedeterminesthe portion of the parametric equations that is actually displayed on the graph.

All right. So far so good?Here’s a figure illustratinghow implicit functions and parametric equations work out in Desmos:

Inequalities

Think that wasquite a list of equations already? Know this: almost all equations can be turned into inequalities by replacing the $=$ sign with $<$, $>$, $\le$ or $\ge$, thereby easilydoubling the amount of graphs onecan plot in Desmos. Just a caveat though: don’tdoitin a command line wherenaming the function is precisely the primary goal.

To get it started, here’s a list of inequalities you can tryout andget the juice flowing:

- Plane: $y<2x$

- Circle: $x^2+y^2 \le 3^2$

- Inside of a Polar Curve: $r<3\cos ^2\theta$

- Area Between Two Functions(e.g., $f(x) \le y \le g(x)$)

- Spacein Between Implicit Functions: $2xy+y^2<4$

And here’s what happened when we throw inthese inequalities into Desmos.

which is pretty cool. And that’s just astart!

Graph Segmentation

When a valid equation/inequality is entered into a command line, Desmos will — by default — plot its graph by assuming the full domain under which the equation/inequality is satisfied. However, thisdoesn’t always yield the desired effects, and there are occasions where it’s preferable notto do so. In which case, one can always choose tosegment the graphby imposing restrictions on theequation/inequality in question — as long as the following syntax rule is being adhered to:

\begin{align*} \text{equation/inequality} \, \{ \text{condition 1}\}\{ \text{condition 2} \} \ldots \end{align*}

For example, to graph the function $x^2$ withthe domain restricted to only the positive numbers, the following line would do:

\begin{align*} y=x^2 \, \{ x>0 \} \end{align*}

Of course, the restriction could have been an inequality on$y$ as well, as in the graph of the function $x^2$ where $y$ is restricted to the interval $[5,15]$:

\begin{align*} y=x^2 \, \{ 5 \le y \le 15 \} \end{align*}

or perhaps an inequality concerning both $x$ and $y$:

\begin{align*} y=x^2 \, \{ x+y<5 \}\{x>0\}\end{align*}

In fact, the restriction(s) could have been any number of equations/inequalities, involving anycombination of thedesignated variables(e.g., $x$, $y$, $r$, $\theta$), with thecaveatbeing that the variables in the restrictions need to becompatible with the equation/inequality they are restricting in the first place (e.g., a polar equationcan only be restricted usingthepolar variables $r$ and $\theta$).

Sounds a bit obscure? Here’s a picture for more info:

Simultaneous Graphing

Tired of plotting very similar graphs one by one? Well, despairnot, for there is a way out when you’re with Desmos. Indeed, if an equation/inequality is expressed in terms of some parameter(s), which is itself definedasa list of multiple numbers, thenmultiple graphs can be created simultaneously for each of these numbers once and for all.

Hmm, what are we talking about here? Here’s an accompanying picture to help us out:

As you can see here, by defining a function with the dummy parameter $a$, which is itself defined as a list with the numbers $1$, $2$, $3$ and $4$, we were ableto graph a total of four functions simultaneously with a mere two lines. Talk about laziness and efficiency!

Andif you’re feeling a bit adventurous, you can certainly try entering an equation/inequality with multiple parameters, each of which isdefined as a list on its own with equal sizes. In fact, this “graphing-in-bulk” method has proved to be a formidable techniqueindrastically slowing down / paralyzing ourcomputers andmobile devices!

On a more serious note though, if you’re looking to exploit the functionalities of Desmos toits fullest, this one is a must. Not only willit automate a graphing process that would otherwise be annoyingly tedious tocarry out, but it also prevent us fromreinventing the wheel when a template for the graphs isalready readily available. Oh, here comes another one!

Animation with UndefinedParameters

When you enter a line of mathematical expression containing anundefined parameter, Desmos will give you to option to include a slider for that parameter, which has the capability of allowingyou toadjust ofits value manually — or even better yet — create an animationout of it byallowing the value of the parameter to increase/decrease automatically.

In particular, theslider will allow you to control the rangeand the increment size of the parameter in question, along withthe speedand thedirection with which the parameter changes. And the reason why it matters, is becauseby having sliders controlling the behaviors of our parameters of interest, it becomes possible for us to create various animated objects such asmovable points, rotatingequationsandanimated regions/boundaries.

For example, to modela particle moving along a sine-wavetrajectory, all we need to do is toembed an undefined parameterintothe coordinates of the sine wave(as in$(a, \sin 2\pi a)+3$ ), before activatingthe slider for the parameter usingthe “play” button. And if the point is meant to be moving along a circular path instead, putting an expression such as $(3\cos a – 5, 3\sin a + 6)$ into the command line would do.Furthermore,ifthe trajectory of a movable point actually defines a function, then Desmos will automatically make the pointdraggable across the $x$-axis, making it easier to manipulate than ever!

But then of course, movable points are just one of the many features animation has to offer.For example,if wewish toinvestigatethe contribution of the different parameters of a depressed cubic equation, then wecan do so by entering $y=x^3+ax^2+bx+c$ into the command line, beforeactivating the sliders for $a$, $b$ and $c$ in any combination we please.Actually, why nottoy around withthe sliders a bit first and observe how the shape of the graph changes during this process!

Andif instead of having one function change its shape, you are interested in seeing several functions under a common parameter moving all at once, then you can — for example— try typing out$y=ax$, $y=ax^2$, $y=ax^3$ into three command lines, activate the slider, and watch as the polynomials move in tandem with pride!

Computing with Desmos

While the interface of Desmos is primarily composed of agraphing grid than anything else, the fact still remains that itwas built fundamentally for computing purpose — and will probably always be.In fact, wewill soon see that Desmos — while obviously well-equipped toperform basic computations — can be hijacked into doinga whole bunch of non-graph-related stuffs such as calculating apartial sum, estimating therootsof a function, determining the value of adefinite integral, or even finding thegreatest common factors froma list of integers!

Elementary Calculations

In Desmos, any mathematical expression involving addition, subtraction, multiplication (*), division (/) and exponentiation (^) can be put into a command line,so that ifthe expression entered contains no variable whatsoever, then the output can becalculated and returned right back to you — usually in a blink of aneye.

In addition, if some functions such as $f$ and $g$ were already being defined in the command lines and we wish to evaluate an expression involvingtheirfunction values (e.g., $4f(15)+2g(0)+5$), then we are warranted to type in that same expression into a command line as well, after which Desmos would be more than happy to comply with our request. What’s more, by using the prime notation,we can even get Desmosto evaluate the derivative of a function at a specific point(e.g., $f'(3)$).

By default, when an equation is entered into a command line, Desmos will give usthe option to display the key points(e.g., intercepts, local maxima, local minima) on the graph — whenever applicable. Furthermore, if wechoose to display these key points, then Desmos will give awaythe coordinates of these points for free as well — usually up to the firstfourdecimal digits if wejust zoom in the graph.

Alternatively, if we are givena function $f$ and weare interestedin making a more accurate estimationfor the coordinates of akey points (e.g., root finding), we can always try typing in $f(a)$ in a new line and activate the slider for $a$, which in turn allows usto control the value of $a$ manually, and see its effect on $f$ in real-time. In fact, if we just configure the step of the slider to $10^{-6}$ (i.e., the smallest valid increment), then weshould be able score a few extradecimals this way.

Furthermore, by naming the mathematical expression we want to compute, we can pass down the output of the computation into a new variable, subsequently using it for other fancier purposes such as building elaborate computations — or graphicalizing the outputof the computations intofiguresand animations.

Lists

When it comes to large-scale computations, it is sometimes more cost-efficient to take the time to constructalist of numbers first, than to manually write down the mathematical expressions one after another. In which case, just know that in Desmos, we can use thesquare-bracket keys to createa list, whose members could eitherenumerated explicitly, or implicitly by typing three dots (as in $[7,8, \ldots ,22]$).

In fact, one can also create a list where the members are listed implicitly but with a non-trivial increment (as in$[2,7, \ldots, 42]$), wherethe increment can be made to be as big as $5635$, or as small as $0.01$ — a flexibility which makesDesmos a powerful tool for defining alargeset of numbers.

Note

In Desmos, the square-bracket keys are specifically conceived for the purpose ofenumerating the members of a list.For delimiters whichserve to group an algebraic expression together, use parentheses instead.

So why exactly do we even bother with creating a list?Because we can use it to run “bulk computations” foreach of the members in the list! And if we intend to use a list on a repeatedbasis,thenwe can choose to assign a name to the list,and pass the name down into thecommand lines for even fancier purposes which include, among other:

- Performing atransformationon the list.

- Simultaneously graphing several functions of the same family.

- Plotting a seriesof points/line/mathematical objectson the graph.

- Calculating thesum of a list — or any other computation which depends on numerically manipulating the members in thelist.

All of which are exemplified in the figure below:

In some occasions, you might it easier to embed the listing and the computations into onesingle command line, but as the task complexitygrows, you might want to consider writing them down in several lines instead to improve legibility and facilitate future references.

Computational Commands

In addition to the standard features offered by a scientificcalculator, Desmos has a bit of extra commands available to a typical programmable calculator as well. For example, we can use Desmos to compute the greatest common factorusing the gcd command — as long as we adhere to the following syntax:

\begin{align*} \gcd (\text{number 1}, \ldots, \text{number n}) \end{align*}

In a similar manner, we can also compute:

- The least common multiple(through the

lcmcommand) - The minimum of multiple numbers (through the

mincommand) - The maximum(through the

maxcommand) - The least positive residue of $a$ under the modulus $b$ (by entering

mod(a,b)) - The number of combinations available whenchoosing $r$ objects from $n$ objects (by entering

nCr(n,r)) - The number of permutationswhen choosing $r$ objects from $n$ (by entering

nPr(n,r)) - The factorial of $n$ (by entering

n!)

For example, if your grandpa offers you the chance of choosing 5 giant gummy bears from the 15 that he has to offer, thenyou can use Desmos to figure out how many ways you can choose the gummies by typingnCr(15,5) into a command line, and be delighted to find out that you actuallyhave $3003$ choices that youcan exercise freely. That is, $20+$ times more choices than gummies!

As for thefactorial, we’ve got an interesting fact for you:Desmos can calculatethe factorial of a number up to $170!$, which iseasily more than double of what can be achieved usinga TI-83 — or any of itsvariants for that matter!

Actually, we are not quite done with the computational commands yet. Here’s five more interesting unary operations— for your pleasure:

ceil(): The ceiling function. It allows you to return the ceiling of a number.floor(): The floor function. It returns the floor of a number. Both ceil and floor are relevant in building thestaircase functions.round(): The rounding function which rounds a number to an integer.abs(): The absolute value function. Using the vertical bar key|is preferred though.sign(): The sign function discussed a bit earlier, which comes in handy in simplifying some obscure mathematical expressions.

Series

If you look closely at the above figure with the Desmos keypad, you mightnotice something that looks like a summation sign, along with the Pi product symbol right next to it. Yep. That’s definitely something Desmos can handle for sure!

For example, let’s say that youwant to estimate the value of the infinite series $\displaystyle \frac{1}{1^2}+\frac{1}{2^2}+\cdots$, then one of the things you can do is to type something like this into the command line:

\begin{align*} \sum_{i=1}^{1000} \frac{1}{i^2} \end{align*}

For the record, the $\sum$ symbol can betyped out using the sum command, after which you will have to use the arrow keys to navigate around and specify the lower/upperlimits. By default, Desmos uses $n$ (instead of $i$, for example) as the main index variable, but you can always change it to another variable at your own discretion — as long as you choose a variable that is not pre-defined for other purposes.

Here, out of curiosity, we decided totoyaround with the upper limit a bit, and found that Desmos seems to top out at $9,999,999$ — just one unit short $10$ millions. That’san astoundingimprovement from the age of programmable calculators!

And it gets even better: by using an undefined parameter as the upper limit and configuring the slider accordingly. we get toturn the output of the computations into an animation — asyou can see in the figure on the left-hand side.Watch asDesmos showcases itsimpressivenumber-crunching powerin real-time!

Alternatively, wecan alsoevaluate the product of a sequence using the prod command, and — if needed — stack up as many summations and products as we like. By nesting one operator inside another, we can also evaluate complexmathematicalexpressions such as those involving double summation or triple product — for instance.

In fact, with just a bit of imagination, we can eventurn the result of computations into ananimated graph, by convertingthe numbers into an animated line segment, or — if we so prefer — convert the numbers into a comparative diagram of our liking!

What`s more, the sum and prod commands are not restricted to the computations of numbers either. For instance, we could try plotting out the $n$th-degree Taylor polynomials of $\cos x$ by leaving$n$ asanundefined parameter, so that once we turn on slider with $1$ as the step-size, we should start to see a bunch of functions flashinglike crazy!

Definite Integrals

Looking to calculate the area below a strange-looking curve? Strugglingto model the total distance traveled by an annoying fly? Or maybe you just want to project your annual revenue for the next year? Either way, the definite integral should have you covered!

In Desmos, the integral symbol $\int$ can be typed out using the int command, after which you can use the arrow keys to navigate around and enter the upper/lower limits. Of course, when defining a definite integral, it’s necessary to include thedifferentialin such a way that the variable of the differential corresponds to the variablein the function you wish tointegrate on.

Similar to the cases with thesummation and product operators, you are also free to stack up as many integral symbols as you like, and use Desmos to evaluate, say, a double integral (e.g., the volume of a geometrical figure) or even a triple integral (e.g., the total mass of a metal rod). But whichever the case, it’s always a good idea to get into the habitofusing parentheses judiciously, so that Desmos understands your expression correctly at each stage of the construction. Otherwise, it’s not our fault if Desmos refuses to parse your expressions like it’s crazy!

So what else can you do with the integral operator? For one,you can trymixing itwith summation and product operators, since they are after all the same kind of operator anyway. Alternatively, you can also use integrals to define an equation or an inequality (e.g., integral function), and do all kinds of stuffs with it such as verifying the FirstFundamental Theorem of Calculus!

Statistics with Desmos

In addition to the standard graphing/computing features available to most graphing calculators, Desmos also has some neat, nativestatistical featuresfor the analytically-driven, data-minded individuals. While it’s certainly no replacement for specialized statistical softwares such as R or SPSS, its capabilities in creating/manipulating tables, computing statistical measuresand providing regression modelsshould be more than enough tocover the basics for the non-statisticians among us!

Tables

While a list of data forms the basis of univariate statistics, having a table of data with multiple columns opens us to the whole new world of multivariate statistics,a branch of science which is becoming increasingly difficultto ignore inthis day and age — wherebig data and information mining proliferates.

And while you’ll most likely not use Desmos for processing big data involving giant tables and fancy metrics, the fact remains you can still createa table in Desmosthroughthe “add item” menu($+$ sign in the upper-left corner), and enter the data manually as you see fit. Being primarily a graphing calculator in nature, Desmos seems to prefer presentinga new table withtwo humble columns by default: the first column $x_1$ presumably for the $x$-values, and the second column $x_2$ for the $y$-values.

Naturally, this setup wouldlead to the use of table as a way of plotting multiplepointsof a function, by first filling out a list ofinput values in the $x_1$ column, followed by redefining the name of the second column as a function of $x_1$ — so thatDesmos can learn to automatically fill in the second column all on its own.

Pro-Tip

If you intend to havethevalues under the first column to be equally spaced, but are too lazy to enter the values yourself manually, then you can auto-fill the first column by pressingEnterrepeatedly — after entering the first two values into thecolumn.

In fact, by creating as many columns as we want, we can extend this point-plotting feature a bit tothree or four functions simultaneously, All we have to do is to make sure that “function columns” are labeledas a function of $x_1$, and watch as Desmos auto-fills the rest of the table and graph for us. No need to ever redo the $x$-values over and over again!

Now, does that mean that you always have to produce a table in Desmos from scratch? Not really. In fact, if you’re familiar any spreadsheet software, you couldimport the table to Desmos via a simple keyboard copy-and-paste shortcut (Ctrl+C to copy, Ctrl+V to paste). While for a small two-column table, importingdata can sometimes be an overkill.For a giant, multi-dimensional table with a dozen of variables, the copy-pasting shortcut can be a true life-saver.

By the way, did you notice the circle icons on the top of mostcolumns? Not only are these icons created every time wecreate a new column, but they are also our only gateway towardscustomizing the appearance of the points on the graph as well. By clicking on the gear iconfollowed by the relevantcircle icon, Desmos will give us the option tochange thecolor of the points under the entire column. Alternatively, we can alsoadjustthegraphing stylebetween the points here, by choosing to have eitherline segments orcurvespassing through them— a feature which comes in handyfordrawingfigures or makingpolygon plots.

To be sure, if you name a column as a function of another pre-existingcolumn, then the values underthe new column will be determined by those under the old column. However, if you choose to labelthe newcolumn as a new variable, then you are in effect making it possible for the entriesunder the column to assume any numerical value.

(for the record, a new variable doesn’t includeany of the pre-defined variablessuch as $x$ and $y$.However, when you attach a new subscript to a pre-defined variable, it does become a new variable as a result.)

Moreover, for each of the columns that are labeled as a new variable, you can makethe points underneath itdraggable throughthe drag setting (accessible again via the gear and circleicons). By configuring the points so that they are either draggable in the horizontal directions, vertical directions, or in every directions, youare essentially giving yourself the choice of manipulating the data visually — which in manycases is more effective thanmanipulating the data numerically.

Descriptive Statistics

Every timewe are givena collection ofnumbers — either in the form ofa list or a columnfrom atable — wecan computesome statistical measuresbased on them. Here’s a list of native, unary statistical commands supported in Desmos:

- Mean: Use the

mean()commandto obtain the arithmetic mean of a list of numbers, which can be defined explicitly (e.g., $\mathrm{mean}([2.5,5.7,15,3]) $), or referred to via a variable name (e.g., $\mathrm{mean}(a_1) $). - Median: Use the

median()command to return the middle number (for a set with an odd number of data) or the mean of the two middle numbers (for a set with an even number of data). - Standard Deviation: use the

stdev()command forsample standard deviation, andstdevp()for population standard deviation. - Mean Absolute Deviation: use the

mad()command to find the mean of all absolute deviations of a list. - Variance: use the

var()command to obtain the sample variance. - Total: use the

total()command to find the sum of all numbers in the list. - Length: use the

length()command to find out the number of data in the list. - Extrema: use the

min()command for the minimum, andmax()for the maximum.

Additionally, here’s a list ofbinary statistical commands supported in Desmos, with slightly more delicate syntax:

- Quantile: To obtain the $p$-quantile of a list $a$, type in

quantile(a,p)into a command line. Note that $p$ must be presented as a decimal between $0$ and $1$. - Covariance: To obtain the sample covariance between the lists $a$and$b$, type in

cov(a,b)orcov(b.a)into a command line. - Correlation: To obtain the Pearson correlation coefficient between the lists $a$ and $b$, type in

corr(a,b)orcorr(b,a)into a command line.

To be sure, the fact that these are about the only native commands supported in Desmos doesn’t mean that these are the only statistical measures we are restricted to. In fact, we could , for example, evaluate the range of a list $a$ by using the command max(a) - min(a),and calculate the Inter-Quartile Range by using quantile(a,0.75) - quantile(a,0.25).

In fact, with just a bit of imagination and ingenuity, it is possible to make out some line charts and bar graphsin Desmos as well. All that is required is some ability in drawing multiplevertical bars and line segments— and perhaps the ability in doing so at the right spots as well. Here’s afigure to keepthe idea of data visualization in the loop!

All in all, producing charts and diagram in Desmos is more of an art than an actual science!Click to Tweet

Regression

When lookingata seriesof points and itsassociatedscatter plot, it’s only natural that we seek to further understandthe nature of relationship — if any — between the two variables in question. In which case, it makes sense that we useregression models to explain and predict the behaviors of one variable from another. In fact, if weapply the “right” regression model to the data, wecan — more often than not —uncoversurprising insights that would have been hardto obtainotherwise.

In Desmos, if you havea table with even just two columns — say $x_1$ and $y_1$ — thenyoucan createa regression model for the associated points to your heart’s content. For a linear regression model, just type in $y_1 \sim mx_1 + b$ into a new line, and Desmos will be more than happy to provide a best-fitting line for you.For a quadratic model, you can type insomething along the line of $y_1 \sim a{x_1}^2+b x_1 + c$, and a parabolashould be ready for you in a blink of aneye. Additionally,if you prefer fittinga higher-degreepolynomial instead, or maybe you just find anexponentialor a logistic modelto be more appropriate,then you arecertainly welcome try out thoseas well — as long as you followthe “regression syntax” outlined a bit above.

What’s more,while the graphing interface of Desmos is built primarily for 2D graphing, that actually doesn’t deter us from doingmultivariate regressioneither. Indeed, if we are given agiant table with4 columns — says $x_1$, $x_2$, $x_3$ and $y_1$ — then wecanfita linear model for these variablesby simplytyping something along the line of $y_1 \simax_1+bx_2+cx_3 +d$ into the command line, so thateven ifDesmos is not properly equipped to plot graphs involving multiple independent variables, we can continue to run multivariate regression as if nothing happened in the first place!

Pro-Tip

While avariable name usually takes the form ofa single letter in Desmos, we are still free to use as much subscripts as we want to. For example, instead of using P as a variable for population size, we might just aswelluse Population instead, thereby eliminating the need of guessing what the variable stands for in the near future.

At the end of the day,whichever regression model wechoose, Desmos will always be glad to present us withthe least-square line for thedata, along its parameters (e.g., slope,intercept) and the correlation/$r^2$of the model. Additionally, we can also use the grey “plot” button(under “residuals” tag) to include the residuals into both the graph and the table — and if we are adventurous enough —pass on the residual variable into the command line again for more detailed analysis!

Miscellaneous

All right. With most of the main features now settled, let’s move on to some other miscellaneous functionalities whichyou might find useful from time to time. In particular, we’ll see how to use Desmos to tweak around thegraph setting, create notes, organizing lines into folders, and make use ofthe saving and sharing functionalities!

Graph Setting

If you look at the upper-right corner of Desmos’ user interface, you should be able to see an icon with a wrenchon it. Why bothers? Because this is the place where you can have access to the Graph Setting menu, which contains a plethora of global settingthat onecan tweak around for practical and not-so-practical purposes.These include, among others:

- Toggling the grid from rectangular form to circular form— or disabling it entirely.

- Labeling the $x$ and $y$-axes.

- Changing the step size of each axis (e.g., using $\dfrac{\pi}{2}$ as step-size when graphing trigonometricfunctions).

- Interpreting the angles in either degree or radian.

In addition, underneath the wrench icon, you should be able to see a $+$ and a $-$ icon. As one would expect, theseicons are used forzooming inandzooming outthe graph, respectively, and when either of the features is exercised, youwill see beneath the $-$ iconan additional home icon, which allows you to return to the default zoom level. Think of it as some sort ofsafety net in case you blow up the graph out of proportion (literally)!

Notes

A note is exactly that: a note for yourself and others looking atyourgraph and command lines. To create a new note, click on thecommandline where you want the note to appear, thentype a" (i.e., the double-quote symbol) to turn the command line into a line for note. While admittedly a non-computationalfeature, a notecan still be used to include anycomment, instruction orexplanations deemed relevant to the graph and thesurrounding computations thereof. In fact, wecan even add a few hyperlinks here and there to spice up the discussion a bit. Just remember tostart the link with ahttpor https prefix though.

Collapsible/Expandable Folders

While primarilya cosmetic feature, a folder is integral tool for organizing your command lines into a coherent set of groups — the latter of which can collapsed or expanded upon demand. Similar to the case with a note, a folder can be created by first clicking on the command line where the folder should appear, and then by accessing the Add Item menuviathe $+$ icon nearthe upper-left corner.Once afolder is created, itcan be given a label, after which a command line can be dragged in or out of the folder with ease, and the triangular arrow iconnext to it can be used to expand/collapse thefolder as one wishes.

Images

Whilegraphical calculators are excellent tools for creating geometrical figures, there are certain times where animage goes beyond simple geometry and needs to be imported from somewhere else instead. Fortunately, this is a feature wellsupported in Desmos, where animage can be added to the graph the sameway a folder is addedtoa command line.

By default, Desmos likes to place an image so that its centeris located at the origin, althoughwe can still move/resize the image by dragging along itscenter or the 8 boundary points surrounding it. In addition, an image’s opacity can be adjusted through the Gear Icon, and itsdimensional values /coordinates of the centercan also be configurednumerically. Heck, we can evensneak insome undefined parametersin them, therebyturning a static image into a flying picture— where the dimension changes from one place to another!

Saving / Sharing Graphs

Findthe mighty power of Desmos appealing and intend to use itextensively in the near future? Then it makes sense that you create an account, and work on your graphswhile logged into the account. Why? Because then you can actually savethese graphs for real, andshare them with other like-minded individuals!

In fact, working on a graph while logged in allows you to give a title to the graph, so that if you decide to save it for later, a simple Ctrl + S will do. On the other hand, any saved graph can also be deleted — if needed to — by hitting the $\displaystyle \times$ button next tothe name of the graph to be deleted.

And if you’re feeling generous enough, you can always share your workwith others by generating a link for the graph — through the greenShare Graph icon near the upper right corner. Remember, Desmos is a cloud-based application after all, which means that every time you save a graph and publish it somewhere online, you are in effect contributing to an ever-growing database ofDesmos modules— all in the name of science and technology!

Closing Words

Ouf! That’s quite a bit on an innocent-lookingonline graphing calculator isn’t it? By the way, if you’ve manage to make it this far, you are already a true hero on your way tobecoming a power user of Desmos! At the end of the day, whether you decide to use Desmos forgraphing, computing, statistics or other purposes, thehope is that you would find a way toleverage thesefunctionalities and adapt them to your own needs. Who knows, maybe you can even turn some of yourinspiration into afruitful, creative process — with perhaps a bit of technical twist along the way!

All right.Ready for the recap? Here’s ajam-packedinteractive table on what we’ve covered thus far:

- Graphing

- Computing

- Statistics

- Miscellaneous

Equations

Preliminaries

| Multiplication |

| Division |

| Greek Letters ($\pi, \theta, \alpha, \beta$) |

| Roots ($\sqrt{}, \sqrt[n]{x}$) |

| Superscript |

| Subscript |

| Ceiling Function |

| Floor Function |

| Sign Function |

| Absolute Value |

| Arrow Keys |

| Parentheses |

Defining Functions

| Functions (in terms of $x$) |

| Functions (in terms of $y$) |

| Trig Functions |

| Exponential Functions |

| Logarithmic Functions |

| Polynomial Functions |

| RationalFunctions |

| Inverse Trig Functions |

| Hyperbolic Functions |

| Function Naming |

| Compounding Functions (via $+$, $-$,$\times$, $\div$, $\hat{}$ and $\circ $) |

| PolarFunctions |

More Equations

Calculus-Related Functions

| Derivative Operator |

| Prime Notation |

| Integral Operator |

| Lower/Upper Limits (Integral) |

| Integrand |

Piecewise Functions

| Syntax (Piecewise Functions) |

| Naming a Piecewise Functions |

| Sign Function |

| $\le, \ge$ Symbols |

Other Equations

| Cartesian Coordinates |

| Implicit Equations (e.g., circle, ellipse, hyperbola) |

| Parametric Equations |

| Designated Variable |

| Adjusting the Domain (Parametric Equations) |

Inequalities

| Planes |

| Circles (Inside or Outside) |

| Polar Curves (Inside or Outside) |

| Area (between two functions) |

| Space(in between the implicit functions) |

Graph Segmentation

| Restriction (Syntax) |

| Restriction on $x$ |

| Restriction on $y$ |

| RestrictionInvolving Both $x$ and $y$ |

| Restriction Involving Other Designated Variables |

Simultaneous Graphing

List

Dummy Parameter

Using Multiple Parameters

Animation

| Undefined Parameter |

| Slider |

| Adjusting Range (Parameter) |

| Increment Size (Parameter) |

| Speed (Parameter) |

| Direction (Parameter) |

| “Play” Button (Slider) |

| Movable Point |

| Multiple Parameters (On a Command Line) |

| Common Parameter (On Multiple Command Lines) |

Elementary Calculations

| Addition |

| Subtraction |

| Multiplication |

| Division |

| Exponentiation |

| Function Values (Evaluation) |

| Derivatives (Evaluation) |

| Key Points (Intercepts, Local Maxima, Local Minima) |

| Displaying Coordinates (Key Points) |

| Root Finding (Using Slider) |

| Naming Expressions |

List

| Creating a List |

| Explicit Enumeration |

| Implicit Enumeration |

| List Naming |

| List Transformation |

| Simultaneous Graphing (Using List) |

| Plotting Multiple Mathematical Objects (Using List) |

| List-Related Calculations |

Computational Commands

| Greatest Common Factor |

| Least Common Multiple |

| Minimum |

| Maximum |

| Least Positive Residue |

| Combination (Counting) |

| Permutation (Counting) |

| Factorial |

| Ceiling Function |

| Floor Function |

| Rounding Function |

| Absolute Value Function |

| Sign Function |

Series

| $\sum$ (Operator) |

| $\prod$ (Operator) |

| Arrow Keys (Navigation) |

| Dummy Variable |

| Upper/Lower Limits (Summation) |

| Animating Series Calculation |

| Nesting Operators |

| Animated Graph (Series) |

| Taylor Polynomial |

Definite Integrals

| Integral Operator |

| Upper/Lower Limits |

| Differential |

| Double/Triple Integrals |

| Integral Function |

Table

| Table vs. List |

| Creating a Table |

| Plotting Multiple Points on aFunction (Table) |

| Creating Multiple Columns (Table) |

| Importing Spreadsheet Data |

| Adjusting Color (for Points in the Table) |

| Graphing Style (Points in the Table) |

| New Variable (as Column Name) |

| Draggable Points |

Descriptive Statistics

| Statistical Measures |

| Mean |

| Median |

| Standard Deviations |

| Mean Absolute Deviation |

| Variance |

| Total |

| Length |

| Minimum |

| Maximum |

| Quantile |

| (Sample) Covariance |

| Correlation |

| Range |

| Inter-Quartile Range |

| Line Charts /Bar Graphs |

Regression

| Scatter Plot |

| Regression Model |

| Linear Regression |

| Quadratic Regression |

| Higher-Polynomial Model |

| ExponentialModel |

| Logistic Model |

| Multivariate Regression |

| Use of Subscripts(Variable Naming) |

| Parameter (Least-Square Line) |

| Correlation / $r^2$ (Least-Square Line) |

| Residual (Least-Square Line) |

Graph Setting

| Grid Setting (Rectangular vs. Circular) |

| Labeling Axes |

| Configuring Step Size |

| Angle Setting (Degree vs. Radian) |

| Zoom In / Zoom Out |

| Default Zoom Level |

Notes

Creating a Note (Keyboard Shortcut)

Purpose (Note)

Adding Hyperlinks

Folders

| Creating a Folder |

| Naming a Folder |

| Adding / Removing Lines from aFolder |

| Expanding / Collapsing a Folder |

Images

| Importing an Image |

| Adjusting Opacity |

| Coordinates of the Center |

| Dimensional Values |

| Moving / Resizing Images (Visually vs. Numerically) |

| Embedding Undefined Parameters |

Saving / Sharing Graphs

| Creating an Account |

| Title (Graph) |

| Saving a Graph |

| Deleting a Graph |

| Generate a Link for the Graph |

And with that, this definitive guide on Desmos has now come to an end. Of course, that doesn’t mean that it’s over yet — for there is yet another way to use Desmos which has great aesthetic and pedagogical value, and that is in the creation of computational drawings!

How's your higher math going?

Shallow learning and mechanical practices rarely work in higher mathematics. Instead, use these 10 principles to optimize your learning and prevent years of wasted effort.

Hmm... Tell me more.

![]()

Math Vault

About the author

Math Vault and its Redditbots enjoy advocating for mathematical experience through digital publishing and the uncanny use of technologies. Check out their 10-principle learning manifesto so that you can be transformed into a fuller mathematical being too.

You may also like

Euler’s Formula: A Complete Guide

Euler’s Formula: A Complete Guide

Laplace Transform: A First Introduction

Laplace Transform: A First Introduction

Leave a Reply

Yeah. It’s pretty cool. Figured out the one with the p-series. 🙂

Reply

Yep. You’ve got it. 🙂

Reply

As a middle-grade student, my knowledge is basic.

How can I add an x-intercept in Desmos? I need an x-intercept, but I only know how to do a y-intercept and Google is failing me. XDReply

Hi Rayray. There is no innate function for x-intercept for good reason — because a function or an equation can have 0 or multiple copies of them.

However, all is not lost though, as Desmos will display the coordinates of the x-intercepts if you click on them on the graph. The coordinates are up to a few decimal points of accuracy, and you can type them into the field if you want to.

Reply

Impressive way presenting Mathematical Ideas so that more & more of target group can grasp them

easily.Reply

Thank you! Graphing and computing using Desmos is quite a topic all on its own, so we thought that keeping everything under one hood would make people life’s easier!

Reply

How can I get more than one decimal place for a slider? I tried to set the step to 0.01, but it does not work.

Reply

Hi Yif. It probably depends on how you’re using the parameter. You can adjust the size of step up to 0.000001 by clicking on the cog icon, and you might have to fill in the upper and lower bounds for that to happen.

Reply

You can do this by making a slider on the graph.

Define the variable you want to use for the slider, eg "a"

Set lower, upper limit and stepsize eg 0, 10, 0.001

Now define a slideable point: (a,1) and check the label box

The point should now appear in your graph. It might not show all the decimals but if you zoom in on the point to have more accuracy in positioning it, additional decimals will appear. I use this for sliders and switches (0-1). That way I can close the sidepanel and still cotnrol the graph.Neat idea Frederik. Thanks for sharing!

Great Job!! It's my first time to use it but extremely satisfied with such explanation. This wonderful to us the mathematics teachers/students.

However, what isn't clear enough is how to copy your graph to other areas of work like Microsoft word.Reply

Hi William. Glad that you find the tool useful. If you’re merely looking to copy an unanimated graph to a word processor, you can either use the share icon on the upper right of the Desmos interface to export the graph as an image, or to simply take a screenshot (which can be done natively in both Mac and Windows).

Reply